“Capital expenditures among companies in the S&P 500 have been growing at a faster pace than stock repurchases for the first time since the first quarter of 2021,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

In the age-old debate around returning capital to shareholders versus investing in the future of the business, does this represent a fundamental shift?

Probably not. A look at macroeconomics – inflationary pressures, supply chain challenges and the like – and legislative policy such as the recently passed buyback tax, helps provide clarity.

Supply chain challenges compel companies to invest in resiliency

Just about any company leader will tell you that the supply chain challenges of the last several years have been unprecedented. Occasional empty shelves are to be expected, but the shortage of nearly everything since COVID, including labor, has driven CEOs to rethink how they make their products.

According to the WSJ, issues with finding workers are driving many companies to invest in software automation to lessen the impact of a tight labor market. PepsiCo has ramped up digital investments to better manage inventory within stores, for example. Alphabet, which sits on a mountain of cash, is buying servers and other equipment to set the stage for future growth.

The fear of being caught short on components, as many businesses have recently, is also driving a “reshoring” movement to regain control of supply chains. A recent survey of executives in the U.S. and Europe, for example, found that “seven out of 10 U.S.-based manufacturing companies are planning to invest in new production capacity closer to their home bases as a result of the global upheavals of recent years.” The interruptions driven by conflict and wide demand swings in the midst of COVID created uncertainty that outweighed the benefits of a minimally expensive, global supply chain.

In a word, companies are investing to become more resilient. A more nimble supply chain allows businesses to respond better to changes in the marketplace, even if it’s a bit more expensive than finding the cheapest places to source their products.

Stock buybacks could lose their luster with a new proposed tax

While investments for the future are important, shareholders still expect near-term returns. Buybacks have historically been a way to both manage dilution and increase shareholder value, but a new tax could cause them to fall further out of favor. The curiously-named Inflation Reduction Act promises to fund investments in energy security and climate change mitigation, paid for by various tax hikes including a 1% fee on stock buybacks.

Other than tax advantages, buybacks have also been popular among company executives because of their flexibility. When a company announces dividend payments, shareholders will come to expect that income, and not take kindly to cuts in these payments. Buybacks, on the other hand, can be initiated at any point without implying that the company will keep doing it quarter after quarter. Another reason for their existence: they limit dilution from executive compensation. When companies grant shares to executives as part of their pay packages, the company then often chooses to repurchase an equal amount of shares to prevent other shareholders from being diluted.

Lastly, of course, repurchasing shares can artificially increase their stock price, as there are fewer total claims to a company’s profits. A recent study showed that S&P 500 companies bought $882 billion of their own shares in 2021, about a quarter of which was for the purpose of managing dilution. That means that about 75% of buybacks from these companies were made solely to increase the share price.

New corporate taxes of any kind can make investors skittish, but according to Bloomberg, the 1% buyback tax is unlikely to significantly impact public stock prices. However, it may tilt the scales in favor of dividends and Capex as a way for companies to increase their value.

Yet the correlation between buybacks and Capex is still murky

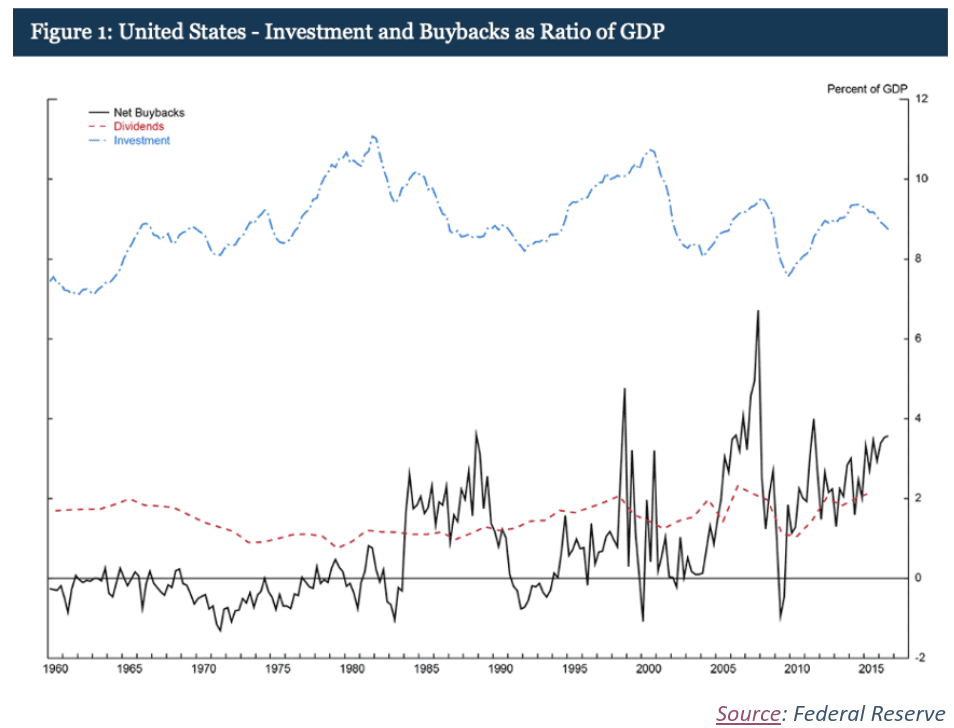

The Federal Reserve chart below compares investment versus capital returned to shareholders from the last 50 years or so. It’s clear that, in times of recession such as 2002 and 2008, investment and dividends/buybacks fall sharply as companies look to preserve cash.

However, the idea that there’s a causal relationship between more investment resulting in lower buybacks, or vice versa, isn’t supported by the data. Coming out of The Great Recession, investment, dividends, and buybacks all rose in tandem off of a low base. From 2014 to 2018, though, investment began to decline while dividends and buybacks continued to rise. Now in 2022, Capex is growing faster than buybacks, further weakening the link between them.

After thoroughly examining this issue a few years ago, the Fed found that its study “provides no evidence either that increasing share repurchases was a motivation for cutting back on investment, or that a lack of investment opportunities was a central reason for boosting repurchases.”

That, however, does not tame the critics who argue that the proportion of net income being distributed to shareholders is unreasonably high, and that companies should be investing more aggressively in their workers, innovation and long-term growth.

Capital allocation in the buyback debate

Whatever the motivation, companies will continue to wrestle with the competing pressures of investing capital in the future of their businesses and returning capital to shareholders (and executives).

For the champions of capital investment, and those who advocate larger Capex budgets, the onus is on them to clearly and accurately forecast the ROI potential of proposed capital projects, and the outcomes – both monetary and strategic – of projects that have been completed. Additionally, visibility into the cash status of projects in the Capex portfolio can be instrumental when decisions need to be made in the face of material changes in business conditions. This is where an enterprise capital allocation solution such as Finario can be a game-changer.

We all know that buybacks will continue, regardless of a 1% tax, and that smart capital allocation remains one of the most essential responsibilities of the CFO’s office. The best performing companies make a point of continuously improving their ability to get the balance right.